|

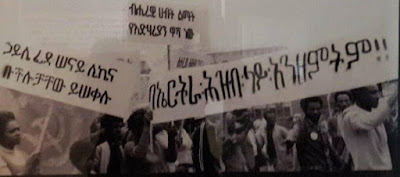

| Popular demonstration during the February 1974 Ethiopian Revolution; photo from the Italian Communist newspaper L'Unita |

I have finally immersed myself in enough readings to start

identifying issues and asking questions. I thought it would be useful

to organize my thoughts into the following “questions,”

identifying themes and patterns for further reading, thought,

analysis, and ultimately, writing. I am neither a trained historian nor academic, but as

someone who has been a leftist activist for a large portion of my

adult life I find a surprising depth of relevance in the story of the

Ethiopian revolution to themes which continue to confront any

movement for revolutionary change.

It's extraordinary to find this exciting, heartbreaking,

fascinating history told not a century after the fact but with the

immediacy of eyewitness observation from participants in living memory.

And in a leftist culture dominated by Eurocentrism and the

increasingly arcane minutiae of early 20th-century Europe,

it's refreshing to find this relevance and inspiration hiding in

plain sight in the relatively recent history of sub-Saharan Africa.

Some of these questions are

intended to be provocative. As I have written before, I do not

consider myself an impartial observer but a partisan of actual

liberatory socialist revolution. After my initial research I find my initial loyalties to the EPRP “side” fundamentally unchallenged, but I think there are some hard issues

that shouldn't be ignored. My investigation has definitely revealed

some sad chapters and difficult questions that I think it would be

dishonest not to address. Some of these questions I obviously have

preliminary opinions on.

Read my original statement of intent about this blog here.

Follow my reading list here (A work in progress).

(A short key to abbreviations for the unfamiliar appears at the

end of this document)

***

1. Ethiopia before and during its 1970s revolution bore a stark

resemblance to a telescoped version of Tsarist Russia and the Russian

revolution. Unlike the rest of Africa, the failure of colonialism to

subjugate most of Ethiopia for an extended period left a highly

organized indigenous feudal empire intact, containing the growing

seeds of capitalist development in a starkly evident class society

where both an urban proletariat and a rural peasantry were suddenly

becoming self-aware. The revolution snowballed during the lives of

one young generation, forcing that generation to

invent political praxis for itself in a country with

very little

political tradition. Suddenly

exposure to the global Marxist-Leninist left and the civil

rights/Black power movements in the US blossomed into the need to make life-or-death strategical decisions. The EPRP, organized

clandestinely and abroad in 1972 and formally revealed in 1975 is

said to be Ethiopia's first political party of any sort. Ethiopian revolutionaries reached out to China, to the Palestinian resistance, to the socialist countries of the Soviet bloc, and to Arab nationalist regimes for assistance, receiving guns, training, books...and heavy introduction to the internal contradictions of the world's socialist movements. But in the Ethiopian February revolution, it was as though Kerensky himself remained at the helm, simultaneously hijacking and repressing the revolution to prevent an Ethiopian October. What does

the ultimate failure of the revolution teach us about the application

of lessons of classical Bolshevism and other communist trends? Was

this the last possible revolution of this classical type?

2. The Western left’s not-yet-successful reliance on

strategies for socialism involving the development of mass,

essentially reformist workers parties has been historically

counterposed in practice variously by those influenced by Maoism (in

favor of people’s war and rural armed struggle); by those in a

Soviet orbit (in favor of military bonapartism and ex post facto

development of mass organizations); and by anarchists/autonomists (in

favor of urban insurrection or autonomous parallel development). The

EPRP —attacked as “anarchists” by their enemies, though

adhering to Marxism-Leninism — found success as a mass, clandestine

urban party, yet sought unsuccessfully to become a guerrilla

movement. The EPRP deeply influenced mass organizations like trade unions (CELU,

teachers), the Zemacha campaign (mass literacy movement), student

groups (especially in the diaspora); organized clandestine

fractions in the military (Oppressed Soldiers Organization), inside

the Derg, inside Kebeles (formal community centers), inside the

police, an underground revolutionary trade union (ELAMA), an

underground youth organization (EPRYL), and urban and rural military

units. It published several regular underground journals with mass

national distribution and readership and participated where possible in public discussions in

the legally sanctioned press. What does the EPRP’s experience of

organizational models and strategies teach us?

3. Thousands and thousands

of young revolutionaries died at the hands of the Derg regime and its leftist allies, and

targeted assassinations by the EPRP took many lives. Did the EPRP's insistence on armed

struggle provoke the “Red Terror” or was it the correct response

to particularly vicious repression? The EPRP vacillated between

calling the Derg and its civilian leftist allies “fascists” and

pondering overtures of unity with those forces. Was there ever a

basis for unity? Was the Derg “fascist”? What is the

verdict on the lethal sectarianism of the Ethiopian left: EPRP vs.

Meison/POMOA, EPRP vs. anja (factions). What are the historical

verdicts on the cases of Fikre Merid, Getachew Maru and Berhanemeskel

Reda; Senay Likke and Haile Fida; Tesfaye Debessay?

4. The competitive EPRP and Meison originated

organically in the Ethiopian left/student movement, especially in the

diaspora, and found favor in segments of the urban proletariat and

petit-bourgeoisie. Yet both were outflanked by Colonel Mengistu, who

seems to have had no history on the left before the February 1974

revolution. Mass action drove the revolution while political power

was confined to a relatively small collection of players inside the

government and later the military. The relationships between (and

inside) the Derg, the government, the military, and the civilian left

were far more complex than revealed at first glance. How did the Derg

successfully coopt the revolution and check the civilian left? Where

did Mengistu's ideology come from? Mengistu seems to have followed

scripts first from Meison/POMOA and later the Soviet bloc, launching

legitimate (if incomplete) revolutionary reforms like literacy and

land redistribution, while consolidating his personal power through

repeated purges and coups inside the ruling body. LeFort says his

mobilization of the lumpen and declassed peasantry was the key to his

social base outside the military. The one reform he resisted, and

what might be considered the primary demand of the EPRP, was popular

democracy. In a country where most of the competitors for power

claimed to be for socialism, what does this battle over democracy

suggest? Here the Maoist doctrine of “New Democracy” found itself

in direct contradiction to “National Democratic Revolution.” How

was EPRP's call for revolutionary popular democracy against what it

saw as the repeating phenomenon of the African military dictator

different than counterrevolutionary democracy movements in other

socialist countries? In an ongoing revolutionary situation, who or

what is the State? How did the class struggle actually combine and

unfold in the revolution? (Peasantry, Proletariat, Urban

Petit-bourgeoisie, Rural landowning class, Feudal

class/Royalty/Comprador Bourgeoisie, Lumpen Proletariat, National

Bourgeoisie). (Side note: ponder Nicaragua where an

assortment of civilian left groups maintained shifting levels of

opposition and critical support to the post-revolutionary

Sandinista regime in the 1980s).

5. If politics were underdeveloped in

Ethiopia, nationalism was not. Ethiopia resisted Italian invasion twice,

losing its self rule only for the period of 1936-1942. Ethiopia’s

revolution was deeply connected to the struggles of national

minorities. Like Russia, Ethiopia is a country of diverse national

identities historically dominated by a single ethnic group. Rene

LeFort calls Eritrea (and the relationship of Eritrea to Ethiopia is up for discussion) the “crucible” of the Ethiopian revolution,

citing a more developed political tradition in colonial Eritrea and

noting the dominance of ethnic Eritreans in the general Ethiopian

radical milieu. Wallelign Mekonnen’s groundbreaking paper on the

national question is virtually the founding document of the Ethiopian

civilian left (and Wallelign's death in a 1972 airplane hijacking is a portent of future tragedy). EPRP attempted to negotiate this minefield, and yet

ultimately found itself at odds with TPLF and EPLF, despite endorsing

Eritrean independence. Today’s Ethiopian federalism, widely seen as

the oppression of the whole nation by the Tigrayan minority ethnic

group, makes nobody happy: unrest involving national minorities like

the Oromo people is today again dominating headlines. Upon the overthrow of the Derg, newly independent

Eritrea promptly found itself at war with its long-term allies in the former

TPLF. What are the lessons here regarding self determination, multi-ethnic

states, and the relationship of political to ethnic conflicts? Is there

any conflict between the consciousness of national liberation and the

consciousness of socialism?

6. Ironically, the avowedly socialist Derg

remained military supplied by the United States for its first two years in power. After

it eliminated the civilian left, the Derg thoroughly coopted socialism

in a statist model a la Eastern Europe, only to abandon

socialism as the Soviet Union floundered, on the eve of itself being

displaced, in the very late 1980s. The Derg was overthrown by the TPLF, the

core of which was the cadre of MLLT, which upon assuming power in

turn abandoned Marxism-Leninism and allied with the United States.

Though some argue little continuity with the classic EPRP suppressed

by the Derg remains, today's EPRP factions have officially renounced socialism.

EPLF-ruled independent Eritrea is ranked (at least by its enemies) as

among the most repressive states on the planet. The “People's

Republic” of China is developing a massively predatory relationship

with Ethiopian industry and agriculture. What are the legacy and

prospects of three failed attempts at socialist power for the

liberatory project promised by socialism to the future of Ethiopia? By 1978, the two main wings of the civilian left now both in opposition to the Derg (as well as to each other), and the ruling Derg itself, all used the iconic hammer and sickle as their symbol. Addis Ababa's massive Lenin statue, built by a regime that arguably had little in common with Lenin's actual ideology, was pulled down by crowds in 1991 celebrating legitimate liberation from tyranny.

Is the well poisoned?

7. It wouldn’t be an overstatement to

say that imperialism has wreaked havoc on the Horn of Africa for well

over a century. Did Italian imperialism import class consciousness

and post-feudal political consciousness via Eritrea? The Ethiopian

royalty earned respect for its resistance to Italian imperialism in

both the 1890s and the 1930s, and used that reputation to attempt to

outflank “African socialism” as a pro-American pole in

continental politics during the independence wave of the 1950s and

1960s. The royalty's domestic reputation began to fail only in the

late 1960s, collapsing in the wake of famine in the early 1970s. US

imperialism and the Soviet Union abruptly swapped sides between

Ethiopia and Somalia in 1976-1977; and then the US switched sides

again after the fall of both the Ethiopian and Somali regimes in the

early 1990s, turning Somalia into a collection of failed states,

ethnic enclaves, and bases for reactionary Islamic fundamentalists,

and turning Ethiopia into a proxy for regional US military power. Chinese

capital (imperialism?) appears a significant motor force in Ethiopia

today. Cuba’s intervention in Ethiopia against Somali invasion was

decisive, yet not extended to the Eritrean front, eventually

resulting in Eritrean secession. Leftist opposition groups in

Ethiopia in the 1970s found themselves in the middle of a hot battle

in the Cold War, ideologically challenged by being targeted by both

imperialism and the Soviet bloc. What are the prospects for

independent national struggle in a world dominated by neocolonialism,

imperialism, social imperialism, and neoliberalism?

8. Many people, unfortunately, in my opinion, including far too

many leftists, view history as the progression of actions of great

(or terrible) men. To look at the Ethiopian Revolution as merely the

story of Mengistu Hailemariam is I think to make a serious

misjudgment of how history happens, of how, in this case, the

Ethiopian revolution unfolded. He was a key figure, for sure, and

certainly for a moment triumphant, and more than a little villainous.

But what Marxism teaches us about the people being the motor force of

history, this is actually true: What the focus on Mengistu reveals to

me, at least, are all the ideological weaknesses of what I would call revisionism (and

let me say here clearly that I reject out of hand the term

“Stalinist”): the post-war Soviet top-down method of socialism by directive, military

force, and the willful wishful thinking of too small a political

minority. This unfolded repeatedly (and ultimately unsuccessfully and

often tragically) in the third world: South Yemen, Afghanistan,

Benin, Burkina Faso, Madagascar, etc. It's true that 20th-century

socialism was ultimately politically outgunned by Western

imperialism, but I think that the broadly-defined pro-Soviet project

of state socialism also collapsed worldwide under the weight of its own

contradictions. (Ironically given what, in my opinion, is socialist

Cuba's problematic role in Ethiopia, I think the survival of Cuban

socialism into the 21st century is in fact a positive counter example

of how important mass popular support for a revolution actually is). It seems that

EPRP's leaders were too busy living their moment of

history in a fiery flash to deliver ideological or theoretical

innovation at their high watermark, at least from the perspective of

my initial investigations, and without knowledge of Amharic. Few survived to have the benefit of

hindsight. Survivors writing today have focused on righting the

historical record, or apologizing for their actions, or preserving

the memory of what was lost: most seem pretty adamant in their

ideological renunciation of the old EPRP's values. So the final

questions are left to us, observers from a geographic and historical

distance: Is there an overarching lesson from the Ethiopian

revolution for the revolutionary project as a whole? What would

actual revolutionary democracy look like? How, next time, do the good

guys win?

I would be interested to exchange ideas with anyone who has studied this revolution.

Notes:

EPRP: Ethiopian People's Revolutionary

Party

Meison: All-Ethiopian Socialist Movement

POMOA:

Provisional Office of Mass Organization Affairs

TPLF: Tigray

People's Liberation Front

EPLF: Eritrean People's Liberation

Front

MLLT: Marxist-Leninist League of Tigray

CELU:

Confederation of Ethiopian Labor Unions

Derg: Amharic for “committee,” a group of military officers who seized power in 1974